1863–1944

Movements

Occupations

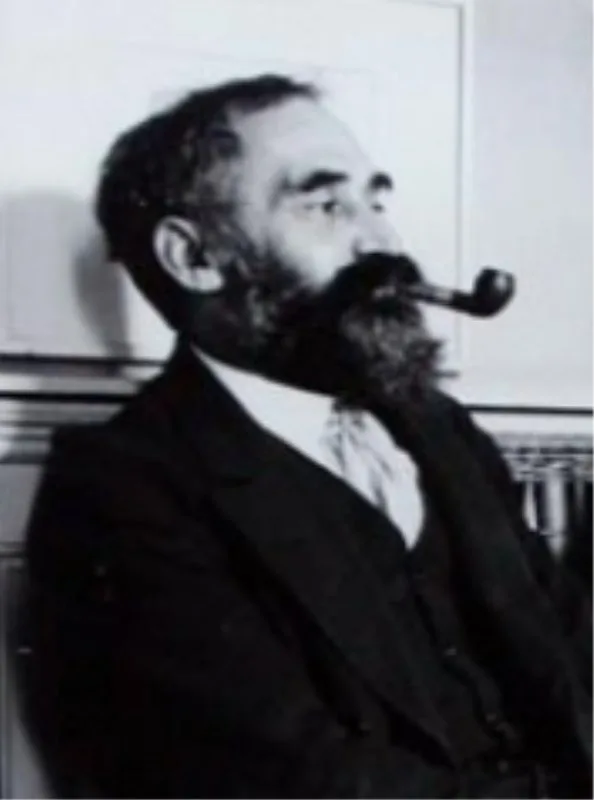

Lucien Pissarro (1863–1944) stands as a unique bridge between French Impressionism and British modernism, successfully navigating multiple artistic movements and mediums throughout his seven-decade career. Born in Paris as the eldest son of the celebrated Impressionist painter Camille Pissarro, Lucien inherited not only his father's artistic talent but also his commitment to innovation and experimentation. His life's work encompassed landscape painting, printmaking, wood engraving, and book design, making him one of the most versatile artists of his generation. After training alongside his father and the Impressionist circle—including close contact with Cézanne, Gauguin, Seurat, and Signac—Lucien developed a distinctive style that synthesized Impressionist observation with Neo-Impressionist technique. In 1890, he made the momentous decision to settle permanently in London, where he would spend the remainder of his life. This geographical shift proved transformative, as Pissarro became instrumental in introducing Post-Impressionist ideas to British audiences and played a founding role in the Camden Town Group, one of Britain's most important early twentieth-century art movements. Perhaps equally significant was his contribution to the Arts and Crafts movement through the Eragny Press, which he founded with his wife Esther in 1894. Inspired by William Morris's Kelmscott Press, the Eragny Press produced thirty-two exquisitely crafted books over two decades, featuring Lucien's innovative color woodcuts and demonstrating his belief that fine art and applied arts should not be artificially separated. Through his painting, printmaking, teaching, and publishing, Lucien Pissarro created a legacy that extended far beyond his famous family name, establishing himself as a crucial figure in the cultural exchange between France and Britain during a pivotal period in modern art's development.

Lucien Pissarro was born on February 20, 1863, in Paris, the eldest of seven children of Camille Pissarro and Julie Vellay. His childhood was steeped in art from the earliest age, as the Pissarro household regularly received visits from the leading artists of the Impressionist movement. Young Lucien grew up surrounded by paintings-in-progress, artistic discussions, and the creative ferment of one of art history's most revolutionary periods.

His early education was unconventional by contemporary standards. Rather than attending formal art academies, Lucien received instruction directly from his father, who believed in learning through observation and practice rather than academic tradition. This informal apprenticeship exposed him to Impressionist techniques and philosophy during the movement's most dynamic years. He witnessed firsthand the preparation for Impressionist exhibitions and absorbed the group's commitment to painting modern life and capturing the effects of light.

During these formative years, Lucien also benefited from contact with his father's closest associates. Paul Cézanne, who frequently worked alongside Camille Pissarro in the 1870s, became something of an artistic uncle to the young Lucien. Paul Gauguin was another frequent visitor, and the young artist observed their experiments with color and form. These early experiences provided Lucien with an artistic education that no academy could match, grounding him in the Impressionist tradition while exposing him to the diverse personalities and approaches within the movement.

By the early 1880s, Lucien began developing his own artistic voice, just as Impressionism itself was evolving. In 1885, Camille Pissarro encountered the work of Georges Seurat and became fascinated by the scientific approach to color that would become known as Neo-Impressionism or Pointillism. Father and son embraced this new technique together, both exhibiting Neo-Impressionist works at the eighth and final Impressionist exhibition in 1886.

For Lucien, Neo-Impressionism offered a systematic approach to the Impressionist goal of capturing light and color. The technique involved applying small dots or strokes of pure color to the canvas, allowing the viewer's eye to optically mix them rather than physically mixing pigments on the palette. This method aligned with contemporary color theory and gave Lucien's work a distinctive shimmer and luminosity. He also exhibited with the avant-garde Belgian group Les XX in Brussels, gaining recognition beyond Paris.

During this period, Lucien also began experimenting with printmaking and illustration, creating wood engravings for French publications. This work in graphic arts would prove crucial to his later development, as it introduced him to the technical challenges and aesthetic possibilities of working in black and white and in multiple colors through successive printings. These skills would later prove invaluable when he established his own press.

By 1890, however, Lucien faced a crossroads. While he had achieved some success in Paris, he struggled with the city's competitive artistic environment and sought new opportunities. When invited to visit England, he made the journey that would change his life forever.

Lucien first visited England in 1883 and 1890, but it was his 1890 visit that proved decisive. London offered both professional opportunities and personal fulfillment. The English art world was becoming increasingly receptive to French Post-Impressionism, and Lucien found he could serve as a valuable intermediary, introducing British audiences to continental developments while establishing his own reputation.

In 1892, Lucien married Esther Levi Bensusan in Richmond, Surrey. Esther came from an Anglo-Jewish family and shared Lucien's artistic interests and socialist sympathies. The marriage proved to be not only a loving partnership but also a crucial artistic collaboration. Esther possessed linguistic skills, literary knowledge, and practical abilities that complemented Lucien's visual artistry, and together they would embark on their most ambitious project: the Eragny Press.

The couple settled in Epping, Essex, where on October 8, 1893, their only child, Orovida Camille Pissarro, was born. Orovida would herself become an accomplished artist, continuing the family's artistic legacy into a third generation. During these years, Lucien continued to paint landscapes in the Neo-Impressionist manner, often depicting the English countryside with the same careful attention to light and atmospheric effects that his father brought to the French landscape.

In 1894, inspired by William Morris's Kelmscott Press and the Arts and Crafts movement's ideals, Lucien and Esther founded the Eragny Press. Named after the village of Éragny-sur-Epte where Camille Pissarro lived, the press represented Lucien's most significant contribution to the Arts and Crafts movement and demonstrated his commitment to the integration of visual and literary arts.

The Eragny Press distinguished itself through several innovations. Unlike Morris's primarily black-and-white publications, Lucien pioneered the use of color woodcuts in book illustration, creating multi-block prints that brought vibrant hues to the page. He designed typefaces, borders, and illustrations, overseeing every aspect of production with meticulous care. The first publication, 'The Queen of the Fishes' (1894), featured colored woodcuts and handwritten text, setting the standard for the press's subsequent output.

Over the next twenty years, the Eragny Press produced thirty-two limited-edition books, each a masterpiece of design and craftsmanship. Titles included works of poetry, fairytales, and classic literature, all unified by Lucien's distinctive visual aesthetic. He created original wood engravings and color woodcuts for each volume, developing a technique that combined the precision of wood engraving with the coloristic richness of his painting. The books featured his specially designed 'Brook' typeface, modeled on Nicolas Jenson's fifteenth-century Venetian types.

The Eragny Press books are now highly prized by collectors and recognized as among the finest examples of private press printing from the Arts and Crafts era. The press closed in 1914 with the outbreak of World War I, but its influence on book design and illustration extended far beyond its twenty-year operation.

In 1907, Walter Sickert invited Lucien to join the Fitzroy Street Group, an informal association of progressive artists who met weekly in Sickert's London studio. This connection led to Lucien's involvement in founding the Camden Town Group in 1911, one of the most important developments in early twentieth-century British art. The group, which included Harold Gilman, Spencer Gore, and Charles Ginner among others, sought to develop a distinctly British form of Post-Impressionism.

For the younger British artists in the Camden Town Group, Lucien represented an invaluable living link to the origins of Impressionism and Neo-Impressionism. His father Camille had been a founding Impressionist, and Lucien had personally known Seurat, Signac, and van Gogh. This firsthand connection to French modernism, combined with his commitment to painting contemporary British subjects, made him a bridge figure between continental and British art.

During this period, Lucien's painting style evolved. While maintaining his commitment to careful observation and luminous color, he moved away from strict Neo-Impressionist technique toward a freer, more varied brushwork. His subjects included landscapes of the English countryside, views of London, and garden scenes, all characterized by a delicate sensitivity to light and atmosphere.

In 1916, Lucien took the significant step of becoming a British citizen, formally cementing his commitment to his adopted homeland. This decision reflected not only his personal integration into British life but also his identification with British artistic circles and his role in shaping British modernism.

The 1920s and 1930s saw Lucien's reputation continue to grow on both sides of the Channel. From 1922 to 1937, he painted regularly in the south of France, returning to the Mediterranean light that had inspired so many Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painters. These trips were interspersed with painting expeditions to Derbyshire, south Wales, and Essex, allowing him to explore the varied landscapes of Britain.

During these decades, his style reached full maturity. While his work remained rooted in Impressionist observation and Neo-Impressionist color theory, it developed a distinctive personal quality—more lyrical than his father's paintings, with a particular sensitivity to the gentle, atmospheric light of the English landscape. His compositions often featured orchards in bloom, rural lanes, and coastal scenes, rendered with delicate color harmonies and careful attention to natural effects.

From 1934 to 1944, Lucien exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy in London, a testament to his acceptance within the British art establishment despite his avant-garde origins. He also maintained connections with French art through exhibitions in Paris and continued correspondence with French artists and critics. This dual identity—French by birth and training, British by choice and citizenship—characterized his entire career.

Lucien Pissarro died in Hewood, Dorset, on July 10, 1944, at the age of eighty-one. His death came as World War II was reaching its climax, a war that had dramatically changed both Britain and France. In his will, he bequeathed a significant portion of his collection to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, ensuring that future generations could study both his own work and the Impressionist paintings he had inherited from his father. His daughter Orovida would continue the family's artistic tradition, painting in a distinctive style influenced by both her father and grandfather.

Artheon Research Team

Last updated: 2025-11-09

Biography length: ~1,847 words

Wikidata/Wikimedia Commons