1840–1916

Movements

Occupations

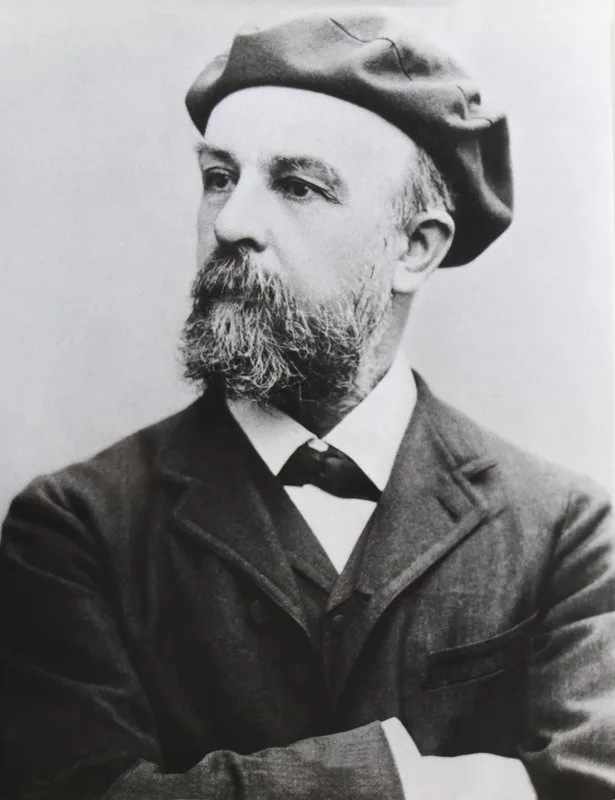

Odilon Redon (1840-1916) was a French Symbolist painter, printmaker, and pastellist whose visionary art bridged the 19th-century Symbolist movement and 20th-century Surrealism. Born Bertrand Redon in Bordeaux on April 20, 1840, he earned the nickname "Odilon" from his mother Odile. His father, who made his fortune in the Louisiana slave trade, conceived Odilon in New Orleans before the family returned to France. Due to fragile health, possibly epilepsy, young Redon spent his childhood with his uncle at the family's winemaking estate in Peyrelebade in the Medoc region, an isolated upbringing he later described as that of a "sad and weak child" who "sought out the shadows." Redon's artistic education proved unconventional and formative. After beginning drawing at age ten and winning a school prize, he studied with Stanislas Gorin starting at fifteen, who introduced him to the Romantic masters Delacroix, Corot, and Goya. His father's insistence on architecture led to brief architectural studies, but failure at the École des Beaux-Arts entrance exams redirected his path. A difficult stint under Jean-Léon Gérôme's overbearing academic instruction in 1864, which Redon described as "tortured," proved incompatible with his emerging vision. Returning to Bordeaux in 1865, he found his true mentors in the eccentric engraver Rodolphe Bresdin, who taught him etching and lithography, and botanist Armand Clavaud, who revealed connections between science and imagination that would profoundly influence his work. From 1870 to 1900, Redon worked almost exclusively in charcoal and lithography, creating what he called his "noirs"—visionary works conceived in shades of black. He believed that "black is the most essential color" and used it to explore dreams, nightmares, and the invisible realm of the subconscious. His noirs employed sophisticated layering techniques: early works combined vine and oiled charcoal with touches of compressed charcoal, while later pieces incorporated fabricated black chalk, conté crayon, and eventually black pastel to achieve rich, velvety surfaces. His lithographic technique, combining transfer paper with direct drawing on stone using waxy crayons, allowed him to reproduce the mysterious atmosphere of his charcoals. Recognition came slowly—his 1878 "Guardian Spirit of the Waters" gained notice, followed by his first lithograph album "Dans le Rêve" (1879). The 1884 publication of Joris-Karl Huysmans' decadent novel "À rebours," featuring a protagonist who collected Redon's drawings, brought him cult status. His series dedicated to Edgar Allan Poe (1882), including the iconic "The Eye Like a Strange Balloon Mounts toward Infinity," and "Homage to Goya" (1885) established his reputation. He exhibited with the Impressionists in their final show (1886) and regularly with Les XX in Brussels. The 1890s marked Redon's dramatic transformation to color. Initially treating completed noirs as monochromatic bases for pastel overlays, he gradually abandoned charcoal entirely after 1900. This shift resulted from friendships with Paul Gauguin, Émile Bernard, and Maurice Denis, as well as Japanese print influences. His pastel technique evolved to include wetting pastel sticks for impasto-like effects, layering with fixative spray, incising, and adding details with conté crayon and graphite. After botanist friend Armand Clavaud's death in 1890, and through friendship with Naturist poet Francis Jammes around 1900, Redon achieved an iconographical breakthrough: vibrant blossoms and foliage illuminated with otherworldly light filled his compositions. Works like "Flower Clouds" (1903), "The Large Window" (1904), and numerous flower vases united earthly observation with ethereal imagination, combining his youthful botanical studies with spiritual expression. These flower pastels dominated his final fifteen years and brought commercial success. Redon received official recognition as Chevalier of the Legion of Honor in 1903, with the French government purchasing his work in 1904. An entire room at Paris's 1904 autumn salon celebrated his achievements. The 1913 Armory Show introduced his work to American audiences. He died on July 6, 1916, having created over 8,000 works. Redon's legacy proves enormous. His noirs profoundly influenced Surrealism—André Breton championed him, and Marcel Duchamp declared, "If I am to tell what my own departure has been, I should say that it was the art of Odilon Redon." His eye-balloon imagery, born from his outsider status, became a Surrealist icon, prefiguring the sliced eye in Luis Buñuel's "Un Chien Andalou." His stated aim to place "the logic of the visible at the service of the invisible" anticipated Surrealist philosophy. Paul Gauguin understood him perfectly: "I do not see why it is said that Odilon Redon paints monsters. They are imaginary beings. He is a dreamer, an imaginative spirit." His works reside in major collections including MoMA, the Art Institute of Chicago, Musée d'Orsay, and the National Gallery London, cementing his position as a visionary bridge between Symbolism and modernism.

Born Bertrand Redon on April 20, 1840, in Bordeaux to a wealthy family (his father profited from Louisiana's slave trade), he acquired the nickname "Odilon" from his mother Odile Guérin, a French Creole woman. Due to ill health, possibly epilepsy, he was sent to live with his uncle at the family's Peyrelebade estate in the Medoc wine region. This isolated childhood profoundly shaped his introspective nature—he later described himself as a "sad and weak child" who "sought out the shadows." He began drawing at age ten, winning a school prize. At fifteen, he studied drawing and watercolor with Stanislas Gorin, a pupil of Eugène Isabey, who introduced him to Romantic masters including Delacroix, Corot, and Goya. Though his father insisted on architectural studies, Redon failed the École des Beaux-Arts entrance exams, ending those aspirations.

In 1864, Redon briefly studied painting at the École des Beaux-Arts under the academic master Jean-Léon Gérôme, but found the experience "tortured" due to Gérôme's rigid emphasis on mimetic representation. The relationship proved incompatible with Redon's emerging imaginative vision. Returning to Bordeaux in 1865, he found his true mentors: the eccentric visionary engraver Rodolphe Bresdin, who taught him etching and lithography and emphasized careful observation in fantastic art, and botanist Armand Clavaud, curator of Bordeaux's botanical gardens, who demonstrated connections between scientific study and imaginative vision. This period established the intellectual foundation for his future work. He also took up sculpture briefly. His studies were interrupted by the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71), during which he served in the military.

After the Franco-Prussian War, Redon moved to Paris and began creating his celebrated "noirs"—visionary works in charcoal and lithography conceived entirely in black. He believed "black is the most essential color" for expressing his feelings and the realm of imagination. His technique evolved from combining vine and oiled charcoal with compressed charcoal in early works, to incorporating fabricated black chalk, conté crayon, and eventually black pastel by the mid-1880s, creating rich, velvety surfaces through sophisticated layering. His lithographic method combined transfer paper with direct drawing on stone using waxy crayons, then scraping away areas to create textured highlights. Recognition came gradually: "Guardian Spirit of the Waters" (1878) brought initial notice, followed by his first lithograph album "Dans le Rêve" (1879). The turning point arrived with Joris-Karl Huysmans' 1884 decadent novel "À rebours" (Against Nature), featuring a protagonist who collected Redon's drawings, bringing him cult status among Symbolist circles. He created major series including "To Edgar Allan Poe" (1882), featuring "The Eye Like a Strange Balloon Mounts toward Infinity," and "Homage to Goya" (1885). In 1886, he exhibited with the Impressionists in their final group show and began regular participation with Les XX in Brussels. His noirs explored dreams, phantoms of insomnia, monstrous fantasies, and the invisible world usually concealed by daylight, establishing him as Symbolism's most visionary practitioner.

The 1890s marked Redon's dramatic shift toward color, though he continued producing noirs until 1900. Initially, he treated fully developed charcoal works as monochromatic bases for pastel, painstakingly creating accomplished noirs which he then obscured with vibrant color. This transitional approach distinguished his method from contemporaries like Fantin-Latour and Degas. The catalyst for this transformation came through friendships with younger artists Paul Gauguin, Émile Bernard, and Maurice Denis, as well as the influence of Japanese prints, evident in his decorative flatness and use of flowers. His pastel technique expanded: he wetted pastel sticks to produce impasto-like strokes, layered pastel with fixative spray and worked each layer by wiping or brushing to develop velvety surfaces, and added black conté crayon and graphite over pastel to outline flowers and add details. After his friend botanist Armand Clavaud's death in 1890, Redon began seeking ways to fuse botanical observation with spiritual expression. In 1899, he exhibited with the Nabis at Durand-Ruel's gallery, signaling his alignment with the decorative, color-oriented aesthetics of this younger generation.

After 1900, Redon abandoned the noirs entirely, devoting himself to pastels and oils in brilliant color. Around 1900, through friendship with Naturist poet Francis Jammes, he achieved an iconographical breakthrough: vibrant blossoms and foliage illuminated with otherworldly light began filling his compositions. His flower paintings dominated this period, combining his youthful fascination with Darwinian biology and botanical observation (cultivated through his friendship with Clavaud) with richly inventive imagination. He created compositions featuring many different types of blooms in effervescent displays, fusing real wildflowers with fantastical species. His pastel technique reached full maturity: he abandoned charcoal underdrawings, alternated layers of pastel with fixative, incised and manipulated surfaces with brushes, and created rich networks of brushstrokes throughout works like "Flower Clouds" (c. 1903). Major works included "The Large Window" (1904), remarkable for its medieval stained-glass window dazzling with pure pastel color, and numerous vases of flowers that "unite the earthly and the ethereal." He also revisited the drowned Ophelia theme repeatedly between 1900-1908, exploring lyrical color using pastel and oils. Official recognition arrived: Chevalier of the Legion of Honor (1903), French government art purchase (1904), and a room devoted to his works at the 1904 Paris autumn salon. The 1913 Armory Show introduced his work to America. These rapturous flower pictures provided his greatest commercial success and dominated his final years until his sudden death from cholera on July 6, 1916.

Artheon Research Team

Last updated: 2025-11-28

Biography length: ~1,847 words

Wikidata/Wikimedia Commons