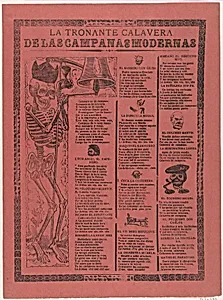

"The Thundering Skeleton of the Modern Bells" is a 1905 print by José Guadalupe Posada that transformed a mundane event—new bells installed in Mexico City's cathedral—into searing social critique. This single broadsheet, sold for a penny on orange paper, captured the paradox of Porfirian Mexico: a dictatorship celebrating technological progress while its people suffered unprecedented economic crisis. The work exemplifies how Posada revolutionized the ancient Mexican calavera tradition, weaponizing skeleton imagery for mass political commentary that would ultimately shape modern Mexican identity and inspire generations of social justice artists worldwide.

1905: A Year of Bells and Economic Collapse

Posada created this print at a pivotal moment. In June 1905, new bells and a clock were installed in the Metropolitan Cathedral tower overlooking the Zócalo, Mexico City's central plaza—a symbol of Church-State power at "the heart of the nation." But 1905 was also the year President Porfirio Díaz's government adopted the gold standard, triggering a 50% currency devaluation that devastated working-class wages while foreign investors bought Mexican businesses at fire-sale prices.

Food prices soared, strikes quadrupled, and Mexico City's death rate became the second-highest in the country. Into this volatile climate, Posada released his "thundering skeleton"—death itself calling out specific occupations including "Don Angel the pawnbroker and Rosita the shoemaker," demanding they "mend their behavior."

Historical Context: From 1905-1910, strikes surged from 29 to 106—nearly quadrupling in five years. The brutal suppression of strikes at Cananea (1906, miners) and Río Blanco (1907, textile workers) became rallying cries against the regime, contributing to the Revolution that erupted in 1910.

The Artist: José Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913)

From Pauper's Grave to Artistic Immortality

José Guadalupe Posada was born February 2, 1852, in Aguascalientes, Mexico, son of a baker in a family of eight children. At sixteen, he apprenticed with José Trinidad Pedroza, learning lithography and engraving—the technical foundation for his life's work.

Despite producing over 20,000 images during his career and working for approximately sixty different periodicals, Posada never achieved financial success or recognition as a fine artist during his lifetime. He died on January 20, 1913, at age sixty from "acute alcoholic enteritis," buried in an unmarked pauper's grave. Seven years later, his unclaimed remains were exhumed and moved to a common grave.

The resurrection of Posada's reputation stands as one of art history's most dramatic reversals. In 1925, French-born Mexican artist Jean Charlot published "Un Precursor del Movimiento de Arte Mexicano," bringing Posada to international attention and positioning him as a foundational figure in modern Mexican art.

The Calavera Tradition: 3,000 Years of Mexican Death Imagery

To understand Posada's genius, one must grasp the calavera tradition he transformed. Skeleton imagery in Mexican culture synthesizes approximately 3,000 years of Mesoamerican beliefs with Spanish Catholic influences.

The Aztecs celebrated death as part of a natural cycle, with month-long festivals honoring Mictecacihuatl, goddess of the underworld. Skull imagery pervaded Aztec life: carved as hieroglyphs, stamped on pottery, displayed on tzompantli (skull racks) at temples. When Spanish conquistadors arrived in 1519, they imposed Catholic traditions of All Saints' Day and All Souls' Day (November 1-2). Rather than eliminating indigenous practices, Mexican culture blended them, creating the modern Día de los Muertos.

Posada's Revolutionary Innovation

While traditional calaveras were reserved for Day of the Dead, Posada used skeleton imagery year-round for any occasion—political satire, news reporting, social commentary. His skeletons were remarkably animated and expressive, engaged in everyday activities: cycling, drinking, working various occupations, even operating printing presses.

His most iconic creation, La Catrina (originally La Calavera Garbancera), shows an elegantly dressed female skeleton wearing an elaborate feathered hat. "Garbancera" referred to indigenous people who sold chickpeas but rejected their heritage to adopt European fashions. Posada intended this as satire of Mexican elites imitating European customs while denigrating their own culture.

The 1905 Print as Social X-Ray

"The Thundering Skeleton of the Modern Bells" operates on multiple levels simultaneously. The print's title—La Tronante Calavera de las Campanas Modernas—links traditional Mexican death imagery with the regime's obsession with modernization.

The Metropolitan Cathedral, built atop the ruins of the Aztec Templo Mayor, had long symbolized Spanish colonial and Catholic authority. Installing modern bells in 1905 represented the union of traditional religious power with Díaz's modernization project, which deliberately modeled Mexico City on Paris with French-style boulevards, Beaux-Arts architecture, and new infrastructure.

Technical Innovation

Printed using zincograph and letterpress on orange paper, measuring approximately 15 by 11 inches, it could be sold for a penny—accessible to even the poorest workers. The orange paper made broadsides visually appealing and helped them stand out when posted on walls.

Popular Distribution

Street vendors (voceadores) sold these broadsides in plazas and markets, often singing corridos while displaying the prints—creating what scholars describe as intrinsically related text, image, and music working together.

How Penny Prints Democratized Art

Posada's collaboration with publisher Antonio Vanegas Arroyo represented more than commercial partnership—it was a radical democratization of art. Before photography, film, or electronic media, broadsides served as "pictorial journalism" and the equivalent of modern social media, documenting events, heroes, villains, social injustices, and daily life from working-class perspectives.

At a time when adult literacy hovered around 32% and was concentrated among middle and upper classes, visual images held outsized importance in communication. The publishing model was ingenious: Vanegas Arroyo produced inexpensive single-sheet publications combining image, text, and verse on cheap colored paper, sold through an extensive street vendor network.

Political Function

While not explicitly calling for revolution (too dangerous in 1905), Posada's prints questioned the moral authority of the Díaz regime and its Church allies, suggested systemic social problems requiring behavioral change, and fostered critical consciousness among working-class viewers. They contributed to the erosion of the regime's legitimacy that would culminate in revolution five years later.

The Great Equalizer: The calavera motif invoked the Mexican tradition that death is the great equalizer—all social hierarchies ultimately meaningless—an egalitarian message resonating powerfully with working-class audiences.

Legacy: From Street Corners to Museums

The resurrection of Posada's reputation stands as one of art history's most dramatic reversals. For over a decade after his 1913 death, Posada remained virtually unknown even as his images circulated throughout Mexico. The pivotal moment came in the early 1920s when French-born Mexican artist Jean Charlot encountered Posada's broadsides sold on Mexico City street corners.

The Muralists' Debt

The three great Mexican muralists each acknowledged profound debts to Posada:

- José Clemente Orozco passed Posada's workshop daily as a child, writing: "This was the push that first set my imagination in motion... this was my awakening to the existence of the art of painting."

- Diego Rivera placed Posada at the center of Mexican history in "Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park" (1947-48), depicting himself as a boy holding La Catrina's hand, with Posada as artistic ancestor to the muralist movement.

- Leopoldo Méndez, founder of the Taller de Gráfica Popular (1937), was considered Posada's direct heir, "the first to adapt the style and motifs of José Guadalupe Posada to political printmaking."

Global Influence

Posada's influence extended globally through multiple channels. By the 1920s, his images reached Moscow; Sergei Eisenstein studied Posada before filming ¡Que Viva México! in 1930. But his impact proved most profound in the United States through the Chicano Art Movement of the 1960s-1970s.

Mexican-Americans reclaiming ethnic identity during El Movimiento embraced Posada as an inspirational figure providing models for social justice imagery. Organizations like Self Help Graphics & Art (East LA, 1971), Mission Grafica (San Francisco), and Instituto Gráfico de Chicago used Posada's accessible printmaking approach for movement posters, flyers, and silkscreens.

Posada Masterpieces in Our Collection

Explore more revolutionary prints by José Guadalupe Posada from the Artheon collection. These penny broadsides transformed Mexican art and inspired generations of social justice artists worldwide.

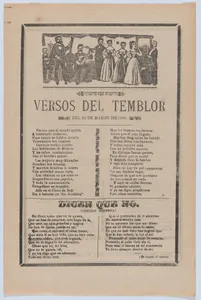

The thundering skeleton of the modern bells

1905

Broadsheet relating to the new clock installed in the cathedral in Mexico City in June 1905

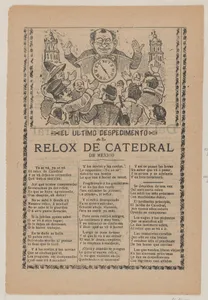

1905

Broadsheet relating to the bullfighting calavera who has arrived at full speed, screaming with much energy

1908

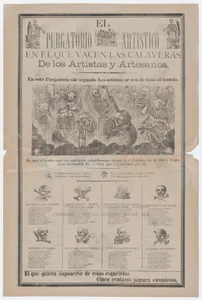

Broadsheet, on recto artist and artisans in hell with objects relating to their profession entitled 'The artistic purgatory, where the calaveras of artists and craftsmen lie', on verso skulls relating to different professions

ca. 1895–1900

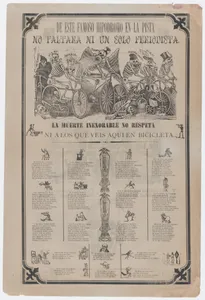

Broadsheet, on recto skeletons riding bicycles entitled 'From this famous hippodrome on the racetrack, not even a single journalist is missing. Death is inexorable and doesn't even respect those that you see here on bicycles'; on verso skeletons buying and selling printed images etc

ca. 1895–1900

Miraculous fountain

ca 1890–1910

Man and woman dancing

ca 1890–1910

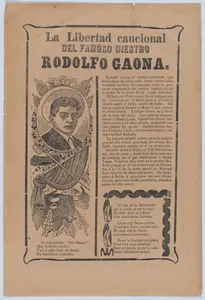

Broadsheet relating to the skillful bullfighter Rodolfo Gaona

ca. 1909

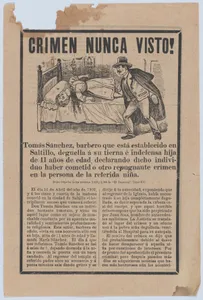

Broadsheet relating to a young girl who was beheaded while her father Tomás Sánchez left her at home alone

ca. 1902

Broadsheet with songs relating to the earthquake that occurred on March 26, 1908

1908

Profile of a man with a beard

ca. 1880–1910

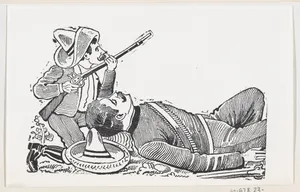

A revolutionary holding a rifle and kneeling to protect a fallen revolutionary

ca. 1880–1910

Visit the Virtual Exhibition

Experience our curated exhibition "José Guadalupe Posada: Printmaker to the People" featuring the artworks discussed in this article and more revolutionary prints from our collection.

Why This Artwork Matters Today

Accessible Art Matters

Posada created work that reached millions, shaped national identity, and influenced generations of artists—all through cheap broadsides printed on colored paper and sold for pennies. Artistic significance doesn't depend on expensive materials or elite patronage.

Art as Documentation

The print illuminates how visual art can serve as historical documentation and political critique simultaneously, recording a specific 1905 event while capturing broader social tensions: currency crisis, labor militancy, moral corruption, class inequality.

Cultural Synthesis

Posada didn't invent calavera imagery—he inherited a 3,000-year tradition synthesizing indigenous and colonial influences. His genius lay in recognizing how this traditional cultural form could address contemporary political crises.

Art and Power

Operating in the dangerous space between tolerated critique and punishable sedition, Posada demonstrated how artists can challenge power even within constrained circumstances—relevant for contemporary artists navigating similar tensions.

Conclusion

"The Thundering Skeleton of the Modern Bells" offers rich opportunities to explore connections between visual art and social history, traditional culture and political innovation, ephemeral media and lasting influence, Mexican national identity and global artistic movements.

The work invites viewers to consider fundamental questions: What makes art "popular" versus "fine"? How do artists balance aesthetic quality with political message? What role does accessibility play in artistic significance? How do cultural traditions evolve while maintaining continuity?

These questions remain as urgent today as when Posada's thundering skeleton first called out from cathedral bells in 1905, demanding a morally bankrupt society mend its behavior before death—that great equalizer—arrives to claim everyone equally, regardless of wealth, power, or pretension.

Further Reading

Books:

- • Ron Tyler, Posada's Mexico (1979)

- • Patrick Frank, Posada's Broadsheets: Mexican Popular Imagery 1890-1910 (1998)

- • Anita Brenner, Idols Behind Altars (1929)