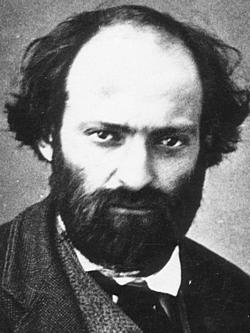

1839–1906

Movements

Occupations

Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) stands as one of the most influential figures in the history of modern art, often called the "Father of Modern Art" for his revolutionary approach to form, color, and pictorial space. Born in Aix-en-Provence to a wealthy banker who discouraged artistic pursuits, Cézanne rejected a legal career to pursue painting, though he remained financially dependent on his family until his father's death in 1886. Cézanne's artistic journey began in Paris where, rejected twice from the École des Beaux-Arts, he taught himself by copying Old Masters at the Louvre and attending the Académie Suisse. There he met future Impressionists including Camille Pissarro, who became his most important mentor. While he participated in Impressionist exhibitions and adopted their brighter palettes, Cézanne's vision was fundamentally different—he sought not to capture fleeting moments of light but to reveal the underlying geometric structure of nature. His famous declaration to "treat nature by the cylinder, the sphere, the cone" encapsulated his analytical approach. Unlike traditional Western art emphasizing a single viewpoint, Cézanne experimented with multiple perspectives within the same painting, a technique that directly inspired Picasso and Braque's development of Cubism. His methodical "constructive brushstrokes"—discrete patches of color creating form without traditional shading—revolutionized how artists understood pictorial space. Working in relative isolation in Provence during his mature years, Cézanne obsessively painted Mont Sainte-Victoire, still lifes of apples and pottery, and ambitious compositions of bathers. These works, initially dismissed by critics, came to be recognized as bridging 19th-century Impressionism and 20th-century modernism. Both Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso acknowledged Cézanne as their true artistic father, and his influence extended through Fauvism, Cubism, and into Abstract Expressionism.

Cézanne's early works are characterized by dark, romantic subject matter executed with heavy impasto and dramatic tonal contrasts. Moving to Paris in 1861, he attended the Académie Suisse and copied Old Masters at the Louvre, absorbing influences from Eugène Delacroix, Gustave Courbet, and the Romantic tradition.

His palette during this period was somber, dominated by blacks, browns, and earth tones applied thickly, often with a palette knife. The subjects ranged from violent scenes to erotic fantasies, reflecting both his tempestuous personality and rejection by the official Salon.

These dense, expressive compositions showed technical ambition but were repeatedly rejected by official exhibitions. Works like 'A Modern Olympia' (1869-70) reinterpreted Manet with abbreviated, expressionistic forms.

A crucial transformation began in 1870 when Cézanne moved to L'Estaque in southern France, partly to avoid military service during the Franco-Prussian War. The Mediterranean light and his deepening friendship with Camille Pissarro fundamentally altered his approach.

Pissarro encouraged him to abandon heavy impasto for smaller, livelier brushstrokes and to brighten his palette. Working side by side in Pontoise and Auvers-sur-Oise, Cézanne adopted Impressionist techniques of painting en plein air and capturing natural light.

He participated in the first and third Impressionist exhibitions (1874 and 1877), though his work stood apart even then. While using Impressionist methods, Cézanne was already more concerned with underlying structure than with transient effects of light.

During the 1880s and early 1890s, Cézanne developed his distinctive analytical approach that would revolutionize Western art. Withdrawing increasingly to Provence, he refined his method of 'constructive brushstrokes'—parallel, methodical strokes that built form through color rather than line or traditional modeling.

His famous still lifes of this period treat apples, bottles, and draperies not as mere objects but as vehicles for exploring spatial relationships and color harmonies. The apparent 'distortions' in perspective were deliberate experiments with multiple viewpoints within single compositions.

Portrait studies, including over 40 paintings of his wife Hortense, approached human subjects with the same analytical detachment as still lifes. Cézanne sought not personality but pictorial problems—the relationship of forms, the architecture of composition.

The Card Players series (1890-92) exemplifies his mature achievement: monumental yet intimate, timeless yet grounded in observed reality, these peasant scenes achieve a classical gravity through purely modern means.

Cézanne's final decade saw his work move toward increasing abstraction while maintaining its foundation in direct observation. Mont Sainte-Victoire became his obsessive subject, painted repeatedly in oils and watercolors that approached pure color construction.

His watercolors, often left deliberately 'unfinished,' revealed his working method with unprecedented clarity—the visible white paper between color patches became integral to the composition, influencing generations of later artists.

The monumental Large Bathers series (1898-1906), left incomplete at his death, synthesized his lifelong concerns: the integration of human figures with landscape, the construction of pictorial space through color alone, the achievement of classical grandeur through modern means.

Recognition finally came in his last years. A major retrospective at the 1904 Salon d'Automne established his reputation, and young artists made pilgrimages to Aix-en-Provence. He continued working until his death from pneumonia in October 1906, following collapse while painting outdoors in a rainstorm.

Wikidata/Wikimedia Commons