1800–1857

Movements

Occupations

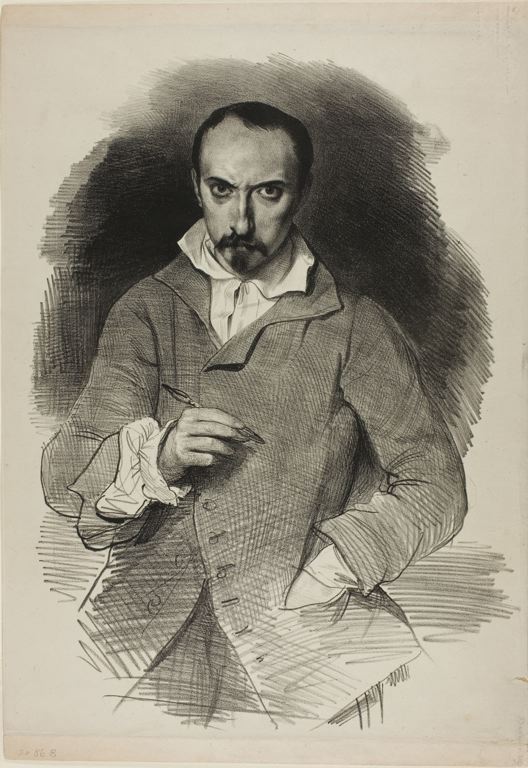

Achille Jacques-Jean-Marie Devéria (1800–1857) was a French painter and lithographer whose prolific output and sophisticated portrait work made him one of the most important visual chroniclers of French Romantic culture. Born in Paris on February 6, 1800, Devéria came of age during the Restoration period and became closely associated with the Romantic movement that dominated French arts and letters in the 1820s and 1830s. His Paris studio on Rue de l'Ouest became a gathering place for the leading writers, artists, and musicians of his generation, and his lithographic portraits documented virtually every major figure in French Romantic culture, from Victor Hugo to Franz Liszt. Devéria's significance extends beyond individual artistic achievement to encompass his role as visual historian of an era. Credited with producing over 3,000 lithographs during his career, he created an unparalleled visual record of early-to-mid 19th-century French cultural life. Charles Baudelaire, the great poet and art critic, praised Devéria's portrait series as showing 'all the morals and aesthetics of the age'—recognition of how completely his work captured the spirit, style, and personalities of Romantic Paris. His illustrations to Goethe's Faust (1828) and romantic novels demonstrated his narrative skill and helped establish the visual vocabulary of French Romanticism. Yet Devéria's career also exemplifies the Romantic artist's relationship to institutional power. In 1849, he was appointed director of the Bibliothèque Nationale's department of engravings and assistant curator of the Louvre's Egyptian department—positions that brought stability but also indicated the establishment's absorption of once-rebellious Romanticism. His final years were spent traveling in Egypt, making drawings and transcribing texts, merging his artistic practice with scholarly documentation. When he died on December 23, 1857, he left behind an extraordinary visual archive that remains essential for understanding French Romantic culture.

Achille Jacques-Jean-Marie Devéria was born on February 6, 1800, in Paris, the son of a civil employee of the navy. This respectable middle-class background provided access to education and cultural opportunities while falling short of aristocratic privilege. His younger brother Eugène Devéria (1805–1865) would also become a painter, creating an artistic brotherhood that would collaborate and support each other throughout their careers.

Achille received formal artistic training from Anne-Louis Girodet-Trioson (1767–1824) and Louis Lafitte (1770–1828). Girodet was one of Jacques-Louis David's most talented students and a key figure in the transition from Neoclassicism to Romanticism, famous for works that combined classical form with romantic subject matter and emotional intensity. This training gave Devéria solid academic foundations while exposing him to the emerging Romantic sensibility.

Training under Lafitte, who specialized in historical and portrait painting, further developed Devéria's skills in figure composition and characterization. This academic preparation proved essential for his later work, providing the technical means to express romantic vision through disciplined craft.

The young Devéria matured during the Restoration period (1814–1830), when the Bourbon monarchy returned to power after Napoleon's defeat. This era saw growing tension between conservative forces seeking to restore pre-revolutionary traditions and liberal, romantic movements pushing for political freedom and artistic innovation. Devéria's generation would channel these tensions into artistic rebellion.

In 1822, at age 22, Achille Devéria began exhibiting at the Paris Salon, the official annual art exhibition that remained the primary venue for artists seeking recognition and sales. His early Salon submissions demonstrated competent academic training while showing increasing romantic tendencies in subject matter and emotional expression.

At some point during the 1820s, Devéria opened an art school together with his brother Eugène. This enterprise served multiple purposes: providing income, establishing their reputation as serious artists, and contributing to artistic education during a period of aesthetic transformation. The school allowed the brothers to develop their pedagogical ideas while building networks within the artistic community.

Devéria's studio on Rue de l'Ouest became a gathering place for the leading figures of French Romanticism. Writers, artists, and musicians congregated there, creating the kind of artistic salon that characterized romantic culture. These gatherings were not merely social but intensely creative, with artists, writers, and musicians sharing works-in-progress, discussing aesthetic theories, and forging the collaborative spirit of the romantic movement.

During this crucial period, Devéria began his systematic documentation of romantic culture through portrait lithography. His 1828 illustrations to Goethe's Faust demonstrated his narrative abilities and helped establish visual interpretations of this seminal romantic text. By 1830, he had become a successful illustrator, publishing lithographs in albums and notebooks that circulated widely among the educated public.

The July Revolution of 1830, which replaced the conservative Charles X with the more liberal Louis-Philippe, ushered in the July Monarchy (1830–1848). This period saw Devéria at the height of his creative powers and productivity, creating the vast majority of his estimated 3,000 lithographs.

Devéria's portrait subjects read like a who's-who of French Romantic culture: writers Alexandre Dumas, Prosper Mérimée, Sir Walter Scott, Alfred de Musset, Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve, Honoré de Balzac, Victor Hugo, Alphonse de Lamartine, and Alfred de Vigny; artists Jacques-Louis David and Théodore Géricault; actress Marie Dorval; pianist Jane Stirling; and composer Franz Liszt. These portraits served multiple functions: documenting famous contemporaries, satisfying public curiosity about cultural celebrities, and creating collectible images for an expanding market.

His lithographic technique benefited from his father-in-law Charles-Etienne Motte (1785–1836), who was himself a significant lithographer and publisher. Motte published many of Devéria's lithographs, providing both technical expertise and commercial distribution. This family connection facilitated Devéria's prolific production by ensuring efficient publication of his work.

Devéria's experience in vignettes and other small-scale decorative imagery influenced his lithographic style, which combined minute detail with atmospheric effect. His work demonstrated technical mastery of the lithographic medium, exploiting its capacity for subtle tonal gradations and varied textures.

Significantly, Devéria rarely depicted tragic or grave themes, distinguishing him from darker strains of Romanticism. His work emphasized beauty, elegance, and refined sentiment rather than Gothic horror or sublime terror, making him appear less intensely Romantic than some contemporaries while still fully participating in the movement's aesthetic revolution.

The Revolution of 1848, which overthrew the July Monarchy and established the Second Republic, brought political upheaval but also new opportunities. In 1849, Devéria received significant appointments: director of the Bibliothèque Nationale's department of engravings and assistant curator of the Louvre's Egyptian department.

These institutional positions marked a transition from independent artist to cultural administrator. As director of the Bibliothèque Nationale's engravings department, Devéria oversaw one of the world's great print collections, responsible for acquisitions, cataloging, conservation, and access for scholars. His practical experience as a printmaker informed this curatorial work.

His role as assistant curator of the Louvre's Egyptian department reflected growing French interest in Egyptology following Napoleon's Egyptian campaign and Champollion's decipherment of hieroglyphics. This position allowed Devéria to combine artistic practice with scholarly documentation.

Devéria spent his final years traveling in Egypt, making drawings and transcribing texts. This Egyptian sojourn merged multiple roles: artist creating visual records, scholar documenting archaeological and epigraphic material, and curator building institutional knowledge. His watercolor technique, which he used extensively for his Egyptian drawings, had been developed through decades of practice.

Achille Devéria died on December 23, 1857, likely in Paris after returning from Egypt. He left behind six children, including Théodule Devéria and Gabriel Devéria, who would continue the family's artistic and scholarly traditions. His vast body of work remains in major collections worldwide, including the Louvre, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, the J. Paul Getty Museum, and the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Artheon Research Team

Last updated: 2025-11-09

Biography length: ~1,591 words

Wikidata/Wikimedia Commons